In the early 1960s, during his visits to various places and meetings with friends, I always loved accompanying my late father, Rashad Mufti. As the youngest son in the family, I was especially dear to him, and he often fulfilled my requests with love and patience.

In keeping with his personal habit, my father would visit Erbil’s Qaisari Bazaar several times a year. Although I hesitate to raise this matter, as it astonished me at the time, shop owners would often ask my father for a small amount of money and place it in their cash boxes. As I grew older, I came to understand that they considered this money a form of tabarruk (blessing), a way to invoke prosperity and ensure the continuity and growth of their businesses.

“Uncle Paulos”

Among the notable figures at that time was the Christian pharmacist Paulos Mirza George, one of the city’s earliest pharmacists. He opened the Northern Pharmacy in Erbil in 1930, located at the beginning of Bata Street. At that time, our home was in the center of the Citadel near where the Kurdistan flag is now raised and next to our family mosque – the Grand Mosque, one of the oldest mosques in Erbil. We lived there until 1964, when we moved to a new home on the Citadel side, near the current governorate building.

“Uncle” Paulos’ house was close to ours, situated across from the home of the late Maroof Saleh Dzayi. His son was a sociable and respected man who frequently visited my father’s diwan – the same library and reception hall that remained open even after my father’s passing in 1992. The diwan serves as a gathering place for guests and has become a valuable resource for university students conducting research.

In the 1970s, during my visits to downtown Erbil, I would often stop by Uncle Paulos’s pharmacy either to buy medicine or simply to greet him. What always caught my attention was how he was always tucked into a corner of the pharmacy, carefully preparing special medications for patients. Undoubtedly, the work of dispensing medicines at that time was in the hands of trustworthy individuals like Uncle Paulos, who were committed to their profession and far removed from any form of deceit.

“Is it permissible to pray in a church?”

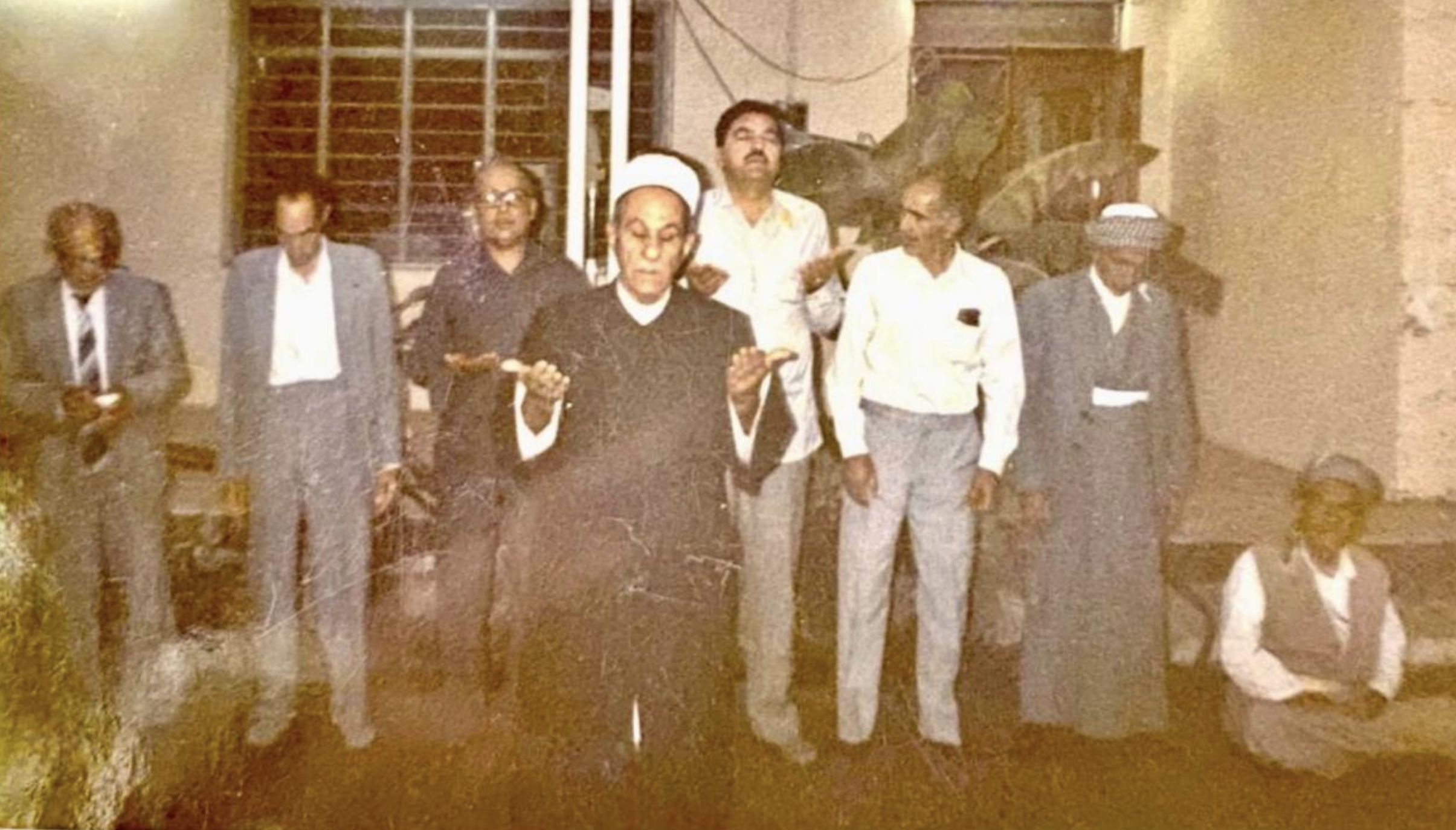

In the mid-1970s, Uncle Paulos passed away. To pay our respects, I accompanied my father and my brother Kanaan Mufti to the condolence gathering at Mar Gorgis Church, the oldest church in Ankawa. The funeral was attended by several notable figures from Erbil, including Judge Qado, Judge Nazim Said Ozeri, Judge Fattah, Judge Maroof Raouf, and Mohsin Haji Saleh.

The Christian ceremony took longer than the Muslim funeral prayers we were used to. The church was filled with Christian attendees as well as Muslim friends of Uncle Paulos. As the hours passed and the Islamic prayer time approached, the call to prayer from a nearby mosque – likely Judge Muhammad’s mosque, which my father had helped establish through donations – reached our ears.

Wearing his religious garb, my father quickly stepped aside within the church hall, spread his cloak on the floor facing the Qibla, and began the prayer with the takbir: “Allahu Akbar.” All eyes turned to him in surprise. Many Christians looked on, wondering: Is this correct in Islam for the mufti and judge of Erbil to pray in a church?

After completing his prayer, my father shook out his cloak and put it back on. At that moment, Judge Abdul Qadir Nour al-Din, my father’s dear friend, approached and asked:

“Rashad Effendi, is it permissible to pray in a church?”

My father replied: “They worship God here, and our religion is one of tolerance. We must embody that tolerance in our actions. We did not come here intending to pray in a church instead of a mosque, but since we are here for Paulos’s funeral and the ceremony has not concluded, it is necessary to pray on time. Doing so also sends a message about the beauty of our faith. These are People of the Book, and it is our duty to protect them. We must build the teachings of Islam on this foundation.”

Word of my father’s prayer and the wisdom he shared spread throughout the church hall and became a topic of discussion across Erbil.

Protecting Christians

After the funeral, on our way back to Erbil, my father recounted an incident from the end of World War I. In 1917-1918, during the Ottoman army’s retreat from Erbil, some officers, incited by extremist voices in the name of religion, attempted to carry out a massacre against the Christians of Ankawa.

When this news spread, the Christians of Ankawa fled their homes, taking refuge in Erbil. Some found shelter in the Citadel’s Grand Mosque, while others fled to the village of Badawa. To prevent the attack, two leading scholars – Mullah Effendi and Muhammad Mufti, my grandfather, both descendants of the great scholar Mullah Abu Bakr (Mulla Kjka, 1778-1855) – issued a fatwa declaring that it was the duty of every Muslim to shelter and protect Christians, warning that anyone who harmed them would face God’s punishment on Judgement Day.

My grandfather’s brother, Ahmad Othman – who was then mayor of Erbil and later the first governor of Erbil District and Sulaymaniyah District and a member of the Iraqi Senate – worked with local tribes to send armed men to defend Ankawa. This was partly done out of the fear of repeating the tragedy that the Turks had inflicted on the Armenians in Turkiye in 1915.

After the situation calmed down, the Christians returned safely to their homes and possessions. That fatwa remained a symbol of religious protection and was often cited by local leaders in the years that followed.

Continuing Muslim-Christian relations

The legacy of coexistence endured thereafter. During Ramadan and Eid al-Adha, Christian clergy from Ankawa were often the first to visit Rashad Mufti at his diwan, followed by Christian figures from the city. Likewise, during Christmas and New Year, my father would visit the church, accompanied by other Muslim scholars like Mullah Abu Bakr al-Hamoundi, Mullah Jirjis Ibrahim, and Mullah Muhammad Khanqah, to offer greetings and well wishes.

I remember clearly that my father once received a letter from His Holiness the Pope at the Vatican, which he would read to guests in his diwan. He had a habit of storing such letters between the pages of his books. Unfortunately, I have not yet located that letter in my archives, though I hope to find it while preparing my book, Imprints of Events, which will be published in both Kurdish and Arabic. When I do, I intend to publish it as a valuable historical document.

I share these events and reflections here to affirm that religious tolerance in Erbil is not new, but has deep historical roots. These should be promoted and celebrated, so that everyone understands that religious figures, through their guidance, ethics, and actions, played an important humanitarian role and were competent leaders of their time. They never lost sight of their national identity regardless of the circumstances and were always ready to defend their homeland, Kurdistan.

Short Biography

Rashad al-Mufti (1915-1992) was a prominent religious and scholarly figure from the city of Erbil. He held several positions, including imam and preacher of the Citadel’s Grand Mosque, judge of Erbil, and head of the city’s Scientific Council. He played a key role in promoting religious tolerance, fostering social harmony, and serving as a trusted authority in resolving community disputes.

Al-Mufti was widely known for his courage and patriotic stances. He notably rejected a request from the Erbil Division Commander to issue a fatwa against the 1962 Kurdish Revolution, and in 1964, he intervened to secure the release of female teachers and students who had been detained for chanting slogans in support of the Kurdish movement.

His cultural and scholarly contributions were equally significant. In the 1940s, he helped promote the Kurdish language through his religious poems. His legacy is commemorated in one of Erbil’s largest mosques, Rashad al-Mufti Mosque, located on the Erbil-Kirkuk road.

He was also the father of Adnan al-Mufti, a prominent Kurdish leader and former President of the Kurdistan Parliament.

Ihsan Rashad Mufti Legal Advisor, Researcher, and Writer