Sheran, also known as Arslan Tash in Ottoman sources, lies about seven kilometers southeast of Kobani and thirty kilometers east of the Euphrates River. While it is an important archaeological site, it is also a village that has undergone significant population growth in recent years, becoming a full administrative district in the 1990s. Equal parts past and present, Sheran has endured through time, a symbol of persistence and permanence.

The site first drew attention in 1883, when Hamdi Bey, director of the Istanbul Museum, visited and documented his observations. Later, in 1928, French archaeologists began large-scale excavations that revealed layers of history beneath the mound: parts of the city’s ancient wall, three gates, temples dedicated to the goddess Ishtar, a palace, and buildings, including the famed House of Ivories, alongside a Hellenistic structure built atop earlier ruins.

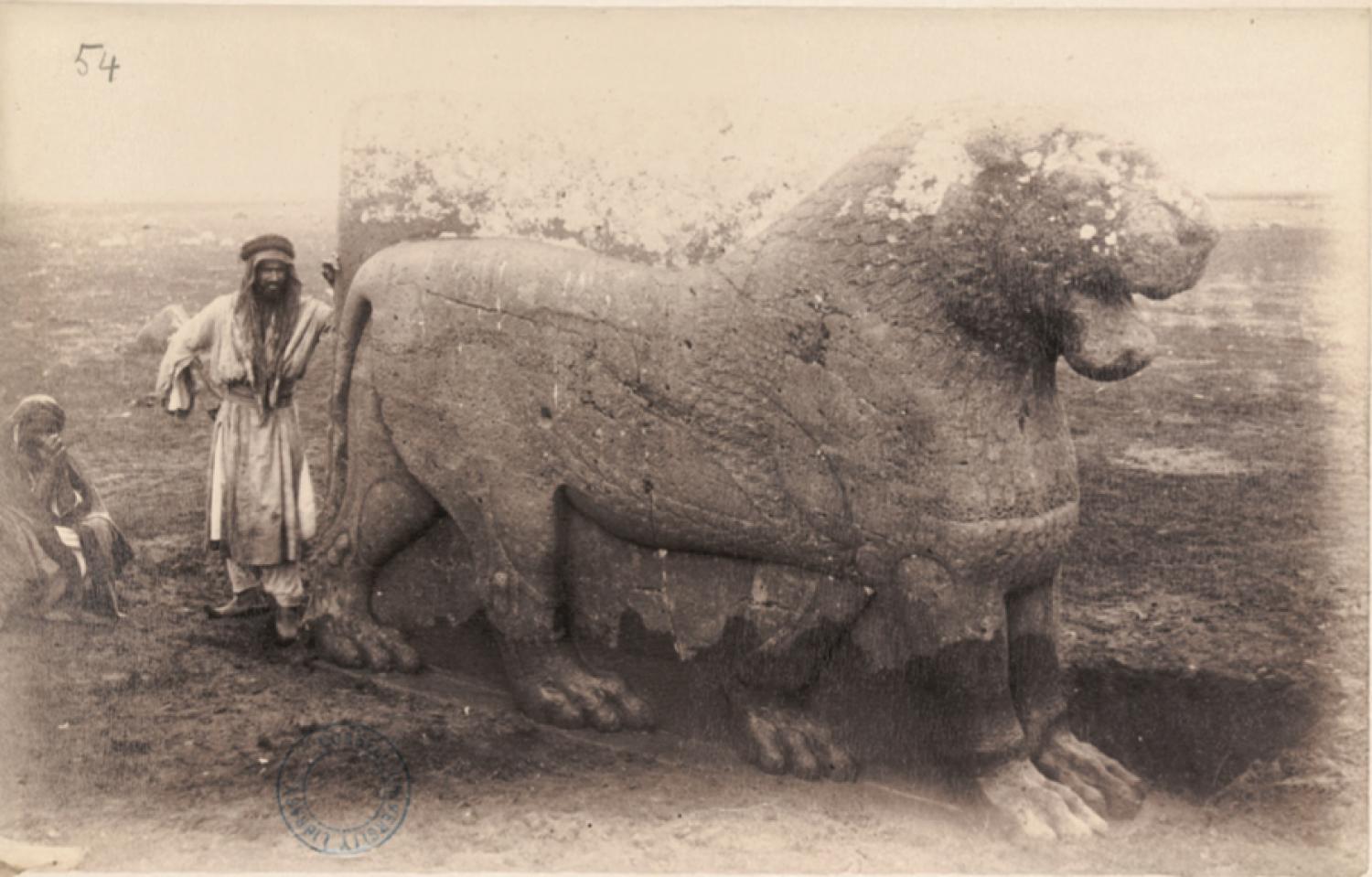

In Assyrian times, Sheran was more than a village; it was a flourishing city called Hadatu. Some scholars link the name to the god Hadad, whose worship spread across the Fertile Crescent, while others trace it to the Aramaic word meaning “new” or “modern.” What remains indisputable is the presence of massive black lions – sheran – that gave the village its name and character. These lions, carved from the volcanic rocks of the Mishtinor plateau south of Kobani, testify to Assyrian artistic mastery and the enduring power of monumental stone art.

Ivories of Sheran: From excavation to the Louvre

Though the lions gave the village its name, it was ivory that brought Sheran global recognition. The House of Ivories – small in size but immense in cultural significance – yielded remarkable artifacts of extraordinary craftsmanship: scenes depicting the birth of Horus, a nursing cow, a woman peering from a window, and a blossoming lotus flower.

These treasures did not remain in Sheran. In 1928, a French excavation team led by Francois Thureau-Dangin, the Secretary General of the Louvre’s Department of Eastern Antiquities, transported the ivories to Paris. Today, a dedicated gallery in the Louvre, the Arslan Tash Collection, houses these pieces. There, the artistry of unknown sculptors continues to captivate visitors, reflecting both Assyrian sophistication and the cosmopolitan influences of the ancient Mediterranean.

Excavations paused for decades and resumed much later. Between 2007 and 2019, an Italian mission under the supervision of Serena Maria Cecchini uncovered additional walls, Assyrian-period strata, pottery fragments, and a seal. Still, much of the site remains unexplored, perhaps because parts of the mound are still inhabited by the village’s residents.

As translator Ahmad Hassan observed in his article, “Examples from the Ivories of Arslan Tash,” these discoveries are more than ivory objects; they are keys to understanding the Assyrian-Kurdish civilization and its integration into wider Mediterranean and Near Eastern artistic currents. At the same time, Dr. Nidhal Haj Darwish notes in the introduction to Arslan Tash, written by Maurice Danan and three other French researchers, the site remains one of the most important archaeological locations in Western Kurdistan (northern Syria).

History and paradox: A Kurdish village in the world’s imagination

Today, standing before the Arslan Tash gallery in the Louvre, one encounters more than ancient artifacts. Visitors witness a small Kurdish village resurrected in the heart of Paris. The basalt lions that once guarded Hadatu’s gates have become images in books, while the ivories that adorned Assyrian palaces now shine under European museum lights.

Yet beneath this display lies a paradox: while Sheran’s treasures rest safely in Parisian halls, the mound itself remains only partially uncovered, still inhabited by villagers walking atop layers of living history.

Sheran is not merely a point on the map; it is a bridge between past and present, East and West. From the Mishtinor plateau to the Louvre Museum, basalt lions and ivories have traveled thousands of kilometers to reshape global perceptions of Assyrian art and Kurdish heritage.

These artifacts tell a story not of fragility, but of creativity and resilience. Black basalt and elephant ivory, hardened and delicate alike, testify that Kurdistan was never a peripheral land; it stood at the heart of ancient civilization. In the Louvre, where millions pass every year, Sheran continues its dialogue with the world: here, on this land, a culture expressed its vitality through art, leaving a legacy that still shines today.

A prolific Kurdish poet, writer and translator.